This post is part of a series on the future viability of ski areas and ski area expansion in the PNW. The previous post explored how the climate and snowpack has changed over the decades and attempted to answer what it may do in the future. This post addresses the political issues and red tape around ski areas specifically in Washington’s Cascades.

Since 1990 Washington’s population has increased from 4.9M to 7.6M in 2022. Despite this, only limited ski area expansions have taken place, certainly not enough to keep up with population growth. As a result, our ski areas are vastly overcapacity. Facing a crisis of overwhelming demand ski areas have resorted to attempting to limit demand through various means in order to control crowding. It lead me to wonder, if the demand for ski areas and winter recreation in general is there, why have all nearly all meaningful expansions seemingly stopped in the past 30 years? What is preventing us from meeting demand and giving everyone access to our wintertime mountains?

Specifically, this post looks at the following issues:

- What land use restrictions prevent development?

- How did we get here?

- What happened to allow or prevent previous expansions?

- What needs to happen for future expansion to take place?

To answer these questions we need to go back to the development era of the 1960s, then through the increasingly restrictive years of the 1970s & 1980s, and finally to the red tape of the 1990s and beyond. It’s a story that involves decades of legislative history, a Supreme Court case, and a whole lot of maps. Given all this, it can seem hopeless that we’ll ever grow beyond the ski areas that we currently have, but as this post explores, there is a present opportunity for Washington to fulfill the demand for winter recreation in the Cascades.

Disclaimer

First off, a disclaimer: I am not a lawyer, ski area operator, or anyone with a background in or credibility on the topics discussed on this page. I am just a passionate skier who loves the PNW and wants to explore how the problems facing ski culture here could be addressed. I am always open to constructive criticism and dialog if you have a more knowledgeable viewpoint to correct me from or just want to discuss these topics further. Please reach out if so (see email in header).

Mapping the Cascades

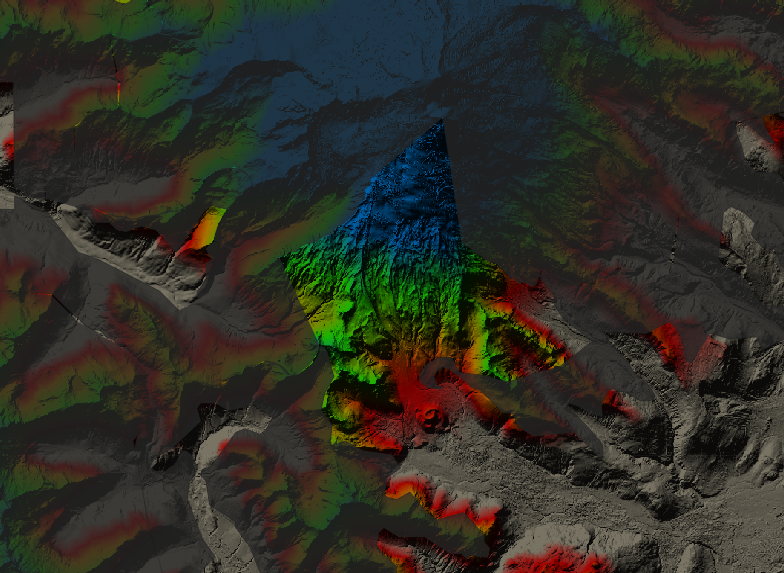

To start, we need to understand the lay of the land so to speak. The first obstacle to any ski area expansion is going to be the land that it is proposed to sit on. The Cascades are a big place and are comprised of a myriad of land restrictions. We have multiple national parks, wilderness areas, national forests, and private land contained within the Cascades. In order to help visualize these better I created a custom map with QGIS. The primary visualization is elevation taken from USGS data and converted into hillshade lighting. The colors correspond to the following elevation bands:

- Brown: < 3,500ft

- Red: 3,500ft - 4,000ft

- Orange: 4,000ft - 5,000ft

- Green: 5,000ft - 6,000ft

- Blue: > 6,000ft

The reason for these cutoffs is that snow coverage is simply too unreliable and inconsistent below 3,500ft to make for good skiing, plus these elevations are already seeing decreased historical snowpack. Investing more in them would not be prudent. Most of our current ski areas sit in the orange & green bands, which works fairly well for the foreseeable future, but the red and orange bands will be the elevations affected soonest by climate change so they should be viewed with caution. The best ski terrain both now and well into the future would be in the green or ideally blue bands.

At first glance, there’s a whole bunch of green and blue terrain on that map. That’s plenty of room for excellent skiing, right? Well, if you enable the national forests layer that starts to narrow down our options. Namely this cuts out North Cascades National Park, Mt. Rainier National Park, and some private land but still leaves quite a bit of forest land as options.

However, the problem of land restrictions becomes abundantly clear when bringing wilderness areas into the mix. In fact, this layer alone eliminates nearly all of the green & blue terrain in the western part of the Cascades. For those that are not familiar with wilderness areas, the 1964 Wilderenss Act created large areas of public lands where no motorized use of any kind of permitted, but more on the specifics of that later.

Still though, there are some areas of high elevation terrain that remain. Nevertheless, enabling the roadless areas layer crosses off virtually all of the high elevation locations on the western slopes of the Cascades. The roadless rule, while not formally a law (yet) prevents the construction of new roads in otherwise undeveloped areas of national forests; more on that later as well.

It’s also worth mentioning here some of our existing ski areas, such as Mt. Baker, are completely boxed in by wilderness & roadless areas. There is virtually no where for them to expand into even if they wanted to.

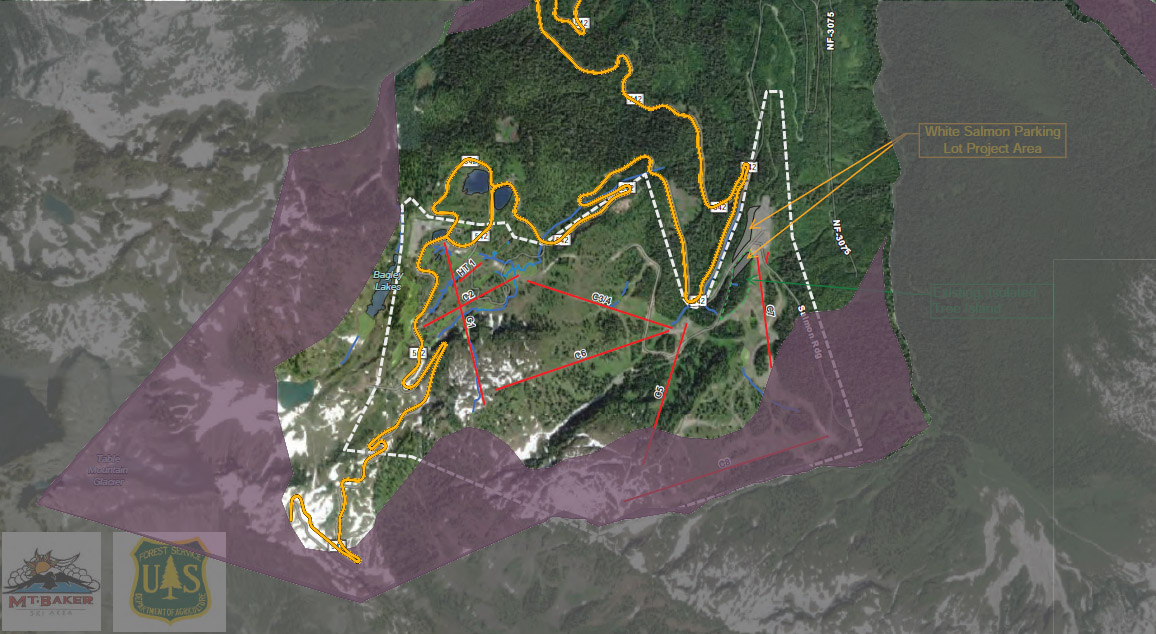

Baker’s permit boundary is outlined in white. The wilderness areas are in grey and roadless areas in purple.

Baker’s permit boundary is outlined in white. The wilderness areas are in grey and roadless areas in purple.

Thus, the biggest obstacle is where would ski areas expand to? The expansion of existing ski areas is difficult let alone the development of a new ski area. But what’s the story behind all of this and is there anything that could be done to expand skiing or are we forever stuck with what he currently have?

How did we get here?

To understand this map better we need a history lesson. What are these wilderness areas and how did we get here? In short, the following events are what crafted the layout of federal lands within the Cascades:

| Year | Event |

|---|---|

| 1899 | Mt. Rainier National Park Established |

| 1937 | Ice Peaks National Park Proposal |

| 1964 | Wilderness Act |

| 1968 | North Cascades National Park Act |

| 1976 | Alpine Lakes Area Management Act of 1976 |

| 1984 | Washington State Wilderness Act of 1984 |

| 1988 | Washington Park Wilderness Act of 1988 |

| 2001 | 2001 Roadless Rule |

| 2007 | Wild Sky Wilderness Act of 2007 |

| 2014 | Alpine Lakes Wilderness Additions and Pratt and Middle Fork Snoqualmie Rivers Protection Act |

| 2021 | The Roadless Area Conservation Act of 2021 Proposal |

Let’s take a look at each of these more in depth to better understand what each of them did and how they built on each other.

In the 1930s, a proposal for the so called Ice Peaks National Park would have extended all the way from Mt. St. Helens to the Canadian border. While support for this proposal never gained enough traction for it to be formally introduced to Congress it did lay the groundwork for the North Cascades National Park proposal which followed.

1964 Wilderness Act

In 1964, Congress passed the Wilderness Act creating the concept of “wilderness areas” within the United States. The intent was to set aside areas of the country to preserve the concept of “wilderness” devoid of mechanization and human development for future generations. What that means is that within a wilderness area no development can take place and no mechanical use is allowed. There are some exceptions for certain wilderness areas mainly based on existing non-conforming uses when they were created but in general no development and no mechanical access is the overarching theme of these areas. The 1964 act begins with the following:

In order to assure that an increasing population, accompanied by expanding settlement and growing mechanization, does not occupy and modify all areas within the United States and its possessions, leaving no lands designated for preservation and protection in their natural condition, it is hereby declared to be the policy of the Congress to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness. For this purpose there is hereby established a National Wilderness Preservation System to be composed of federally owned areas designated by the Congress as “wilderness areas,” and these shall be administered for the use and enjoyment of the American people in such manner as will leave them unimpaired for future use and enjoyment as wilderness, and so as to provide for the protection of these areas, the preservation of their wilderness character, and for the gathering and dissemination of information regarding their use and enjoyment as wilderness; and no Federal lands shall be designated as “wilderness areas” except as provided for in this Act or by a subsequent Act.

What this means for ski areas is that short of an act of Congress to redraw wilderness area boundaries, no development can occur within wilderness areas period.

North Cascades National Park Act

In 1968, the North Cascades National Park (NCNP) was established along with the Pasayten Wilderness. This was not without its fair share of controversy, however. Today, most of the North Cascades is undeveloped and primarily wilderness but when the park was established the future of this area was much more in question. In fact, the NCNP act explicitly authorizes permanent ski lifts to be built in the park, the first national park legislation to do so. The author of the act, Senator Henry M. Jackson, stated:

This is the first park legislation in history to specifically authorize permanent ski lifts within the park.1

There was concern at the time that this legislation was locking up too much land from development and that while wilderness areas were great for the avid outdoorsman, they were not especially accessible for the masses and hence the development of trams and narrow-gauge railroads would be appropriate to allow for recreational access to everyone, year-round. The preservationist organizations at the time objected to some of this development but did support some of it, outside of the park for the skiing at least. For example, the northwest conservation representative of the Federation of Western Outdoor Clubs remarked:

A great many people in our organizations are ardent skiers, but we do not feel that a national park is a proper place for it, particularly when we have already identified at least 15 other sites in the North Cascades are which could be developed for skiing.1

Where these 15 other sites were located may be lost to history but overall these concerns about where ski area development could take place in the North Cascades led the authors of the NCNP act to include a provision on a study being undertaken to identify potential locations within two years of the enactment of the act. This became known as the North Cascades Winter Sports Study. Much more on this later (it’s really interesting stuff!).

Moreover, there was a proposal for three trams to be built in the park. One up Ruby Mountain, another on the west side of Ross lake accessible only by boat, and a third on Price Lake giving a view of the north face of Mt. Shuksan.1 The latter two of these were of questionable value but the one on Ruby Mountain could have been of incredible use for skiing. James Whittaker disagreed on this point1, but given how backcountry gear technology has advanced in the proceeding decades and that Ruby Mountain is a fairly popular ski touring location in the present day, it would appear to refute Whittaker’s opinion on the matter. None of these trams were ever built of course but one can only imagine what may have been for backcountry skiing with a winter tram to the summit of Ruby Mountain.

1968 could therefore been seen as something of the high point for what skiing infrastructure could have been coming soon. NCNP legislation explicitly allowed ski lifts to be built, government studies were required to be undertaken on where to build a new ski area, the conservation groups were on board with development (in certain areas outside of the park at least), and there were proposals for trams to mountains that would be great for ski touring. Unfortunately though, none of this came to be. So what happened?

Wilderness Expansions

A provision in the 1964 Wilderness Act was that within 10 years of the act an inventory of roadless areas of 5,000 contiguous acres would take place. Roadless meaning basically what it says, swaths of land without developed roads. This became known as the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation or RARE. This finished in 1972 but was later found to be insufficient and the analysis was abandoned in favor of a new analysis. This second analysis, known as RARE II, was completed in 1977.2

With the RARE II report complete, this paved the way for wilderness expansions in Washington. Until this point, the Wilderness areas in the Cascades were fairly limited consisting of the Alpine Lakes, Glacier Peak, Pasayten, Goat Rocks, and Mt. Adams wilderness areas. The Washington State Wilderness Act of 1984 greatly expanded the wilderness areas in the Cascades. Namely it created the following wilderness areas:

- Mt. Baker Wilderness

- Noisy-Diobsud Wilderness

- Lake Chelan-Sawtooth Wilderness

- Boulder River Wilderness

- Henry M. Jackson Wilderness

- Clearwater Wilderness

- Norse Peak Wilderness

- Glacier View Wilderness

- Tatoosh Wilderness

- William O. Douglas Wilderness

- Indian Heaven Wilderness

- Trapper Creek Wilderness

It also expanded the Glacier Peak, Pasayten, and Mt. Adams wilderness areas.

What’s interesting about the 1984 act is that the Mt. Baker Wilderness had a section of the actual Mt. Baker carved out to create the Mt. Baker National Recreation Area. This area (pictured below) is a wedge shape extending nearly to the summit of Mt. Baker along its south face. The act explicitly allows for snowmobile use in this area in addition to other recreational uses as such:

The Secretary shall administer the recreation area in accordance with the laws, rules and regulations applicable to the national forests in such manner as will best provide for (1) public outdoor recreation (including but not limited to snowmobile use); (2) conservation of scenic, natural, historic, and other values contributing to public enjoyment; and (3) such management, utilization, and disposal of natural resources on federally owned lands within the recreation area which are compatible with and which do not significantly impair the purposes for which the recreation area is established.

Then in 1988 the Washington Park Wilderness Act of 1988 expanded wilderness areas again. This time, however, the expansions within the Cascades were limited to land already within North Cascades and Mt. Rainier national parks, specifically the Stephen-Mather Wilderness and Mt. Rainier Wilderness. Given that this act effectively converted the vast majority of land in the NCNP to wilderness it seemingly makes the provision in the NCNP establishment act about allowing the installation of permanent ski lifts moot.

The Roadless Rule

Moving on, in 2001 the so called “roadless rule” was added to the Federal Register. The Federal Register being the place of documentation for federal regulations. So while not technically a law carrying the same weight as wilderness areas, the roadless rule effectively protects most of the remaining inventoried roadless land established by RARE II that were not made into formal wilderness areas. The rules of these lands are sort of a light wilderness area in that they allow for motorized use but not development of roads and associated resource extraction with few exceptions.

For the purposes of skiing, well, the roadless rules does seem to, in general, prohibit the development of the expansion and development of new ski areas within inventoried roadless areas:

Road construction and timber harvest would also be allowed for new ski areas, or expansions of existing ski areas outside the existing special use permit boundaries, in inventoried roadless areas provided that the expansion or construction was approved by a signed Record of Decision, Decision Notice, or Decision Memorandum before the date of publication of the rule in the Federal Register (FEIS Vol. 1, 3–226).3

Although being a regulation rather than a law, this is somewhat more flexible and open to interpretation. For example, it does leave the door open to limited ski area expansions under certain conditions:

Under paragraph (a), road construction or reconstruction associated with ongoing implementation of special use authorizations would not be prohibited. For example, all activities anticipated and described in an authorized ski area’s master plan, such as construction or maintenance of ski trails and ski runs, the use of over snow vehicles or off-highway vehicles necessary for ski area operations, including associated road construction, would not be prohibited even if a specific decision authorizing road construction has not been made as of the date of publication of this rule in the Federal Register.3

It also uses wording such as “unlikely” instead of “prohibited” when referring to new ski areas:

Opportunities for some types of recreation special uses may be limited in the future. Developed recreation use and road-based recreation uses in general are more likely to occur at higher densities outside of inventoried roadless areas than under the baseline, since expansion into inventoried roadless areas would not occur. However, roads are rarely constructed into inventoried roadless areas for recreation purposes. The development of new ski areas within inventoried roadless areas would be unlikely.3

Exactly what it allows for and does not allow is honestly somewhat over my head. It may be the type of thing a court would need to decide on. As a rule of thumb of, however, it is likely best to simply consider these lands as not open for ski area development unless proven otherwise.

In 2021, the Roadless Area Conservation Act of 2021 was introduced. While it has not passed at the time of this writing, it would codify the roadless rule into law instead of only being a regulation. Unfortunately, the text of this act does not make what would be allowed for recreational purposes less ambiguous.

That brings us to the present day. A series of wilderness expansions from 1964 to 1988 locked out development from vast amounts of the Cascades. Then in 2001 the roadless rule made it unlikely that most of the remaining land would ever be developed as well. These land use restrictions are the first major obstacle to any ski area expansions happening in the Cascades.

North Cascades Winter Sports Study

As mentioned above, the 1968 North Cascades National Park Act required a study of potential ski areas in the north Cascades. At the time, the creation of the NCNP was fairly controversial, especially from the ski industry as they were concerned that the restriction of these lands would prevent needed expansion of new ski areas. There was also concern raised in the NCNP Act hearings that the act did not adequately address this issue. Hence, the act explicitly required the study of areas either inside or adjacent to the park for the development of winter activities as well as other lodges and campsites:

Within two years from the date of enactment of this Act, the Secretary of the Interior and the Secretary of Agriculture shall agree on the designation of areas within the park or recreation areas or within national forests adjacent to the park and recreation areas needed for public use facilities and for administrative purposes by the Secretary of Agriculture or the Secretary of the Interior, respectively. The areas so designated shall be administered in a manner that is mutually agreeable to the two Secretaries, and such public use facilities, including interpretive centers, visitor contact stations, lodges, campsites, and ski lifts, shall be constructed according to a plan agreed upon by the two Secretaries.4

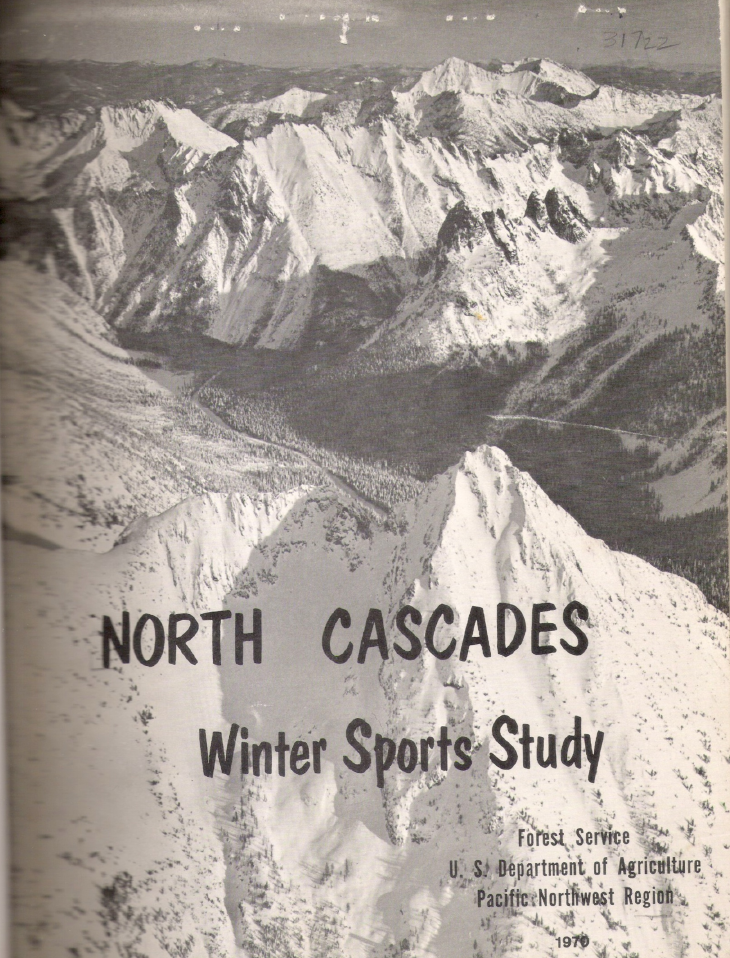

In 1970 the then named North Cascades Winter Sports Study was completed. I found a few scattered references to this study as well as its conclusions around the internet but was unable to find a copy of the actual study. This was until I was tipped off by Lowell Skoog’s Alpenglow Ski Mountaineering History Project bibliography that a copy of the study was in UW’s library. With the help of a UW student, I got my hands on the actual study to reference in its entirety.

If you’re interested, I took the time to scan it into a PDF since it’s a good read and I could not find any other digital copies anywhere. The numbered dots on the map pages are stickers, not printed, which leads me to guess that there were not many copies made. If that’s true, I’m not sure how many copies still exist. Unless there’s a copy sitting in a forest service archive somewhere, the UW one might be the only copy left in existance hence I thought its digital preservation was time well spent.

Having the actual study in hand allowed me to understand the criteria used to assess ski area viability and its overall recommendations. The authors concluded the following three major points:

- The first priority must be expansion of existing ski areas. It hypothesized that over the following 10 years the vast majority of ski demand could be met with expansions of existing sites. The limiting factor to this being sufficient land for parking (hm, sound familiar?).

- The North Cascades are not well suited to large downhill skiing facilities. Rather, they are better suited for ski touring and ski mountaineering and that two of the studied sites, Schriebers Meadows and Washington Pass should be designated as ski touring sites with features such as:

- Tour huts, lodges, or hostels

- Marked trails

- Ski patrol / rescue services

- Mountain guides

- Helicopter transportation

- Rental equipment

- Any new development in the North Cascades must provide an undamaged mountain environment.

Another main theme of the study was that ski areas in Washington will likely never have the mass market appeal that those of Colorado, Utah, or Europe have. This is due to the inconsistent snow quality, comparative lack of winter sunny days, difficult to reach areas, and lack of private land for development of base areas. Even local residents would look elsewhere for longer ski trips. Ski areas in Washington are primarily relegated to local, weekend visitors. Thus, the expansion and new development of ski areas should remain focused on this demographic rather than attempting to lure out of state visitors to large resort style developments.

As for the specific sites, the following characteristics were taken into account when assessing their viability:

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Accessibility | How far from a population center is the site? Either by driving distance or distance from an airport. Is the site accessible via road? Is the road paved? Is it feasible to maintain winter access along the road? |

| Avalanche hazard | Too high of an avalanche hazard would be costly to control. |

| Aspect | North and northeast facing slopes are preferred to limit melt-freeze cycles from sun exposure. |

| Wind | Terrain below treeline provides protection from wind and flat-light conditions. |

| Base elevation | Base elevation should be at least 4,000ft to ensure consistent enough snow needed for commercial ski area viability. |

| Elevation rise | At least 1,500 - 2,500ft of elevation gain. |

| Variety of terrain | A good variety of terrain that would appeal to all levels of skiers. Specifically 20% beginner terrain, 60% intermediate, and 20% advanced. |

| Parking availability | Sufficient land at the base area for parking facilities. If not possible, the ability for trams or railways to transport skiers from a parking facility to the base area. |

| Land status | For a larger development, private land adjacent to the ski area would be needed to fulfill the need for private housing, hotel, and commercial development. |

It is worth noting that the study points out “in the decades to come, the physical limitations or human desire for winter fun will undoubtedly change drastically. Therefore, what today is not feasible, may tomorrow be, and vise [sic] versa.” In the 50 years since this was written that statement has held true. Today we have the benefit of considerably better gear both for alpine skiing and especially alpine touring skiing. This has allowed expert level skiers to tackle terrain that would have been seen as undesirable 50 years ago. This coupled with population growth means that a ski area focused more on expert terrain than a wide variety of terrain could likely still enjoy commercial success. Moreover, chairlift technology is considerably more advanced. We have high capacity, high speed chairlifts, and gondola systems that can span longer distances than in decades past thus opening access to areas that were previously infeasible for development.

With that said, below are the specific sites that the study evaluated:

The conclusions for each of the sites:

| Study | Reserve | Eliminate |

|---|---|---|

| Glacier Basin | Twin Sisters | Dock Butte Basin |

| Schriebers Meadow | Marten Lake Basin | Snowking-Found Creek |

| Cutthroat Pass | Gabrielhorn | Harts Pass |

| Sandy Butte | Liberty Bell | |

| Tiffany Mountain | Stormy Mountain |

Of all these sites, in theory only three of them lie outside wilderness & roadless areas today and would be developable. That is, Schriebers Meadow (thanks to the Mt. Baker NRA carve out in the 1984 law), Dock Butte Basin, and a portion of Sandy Butte.

Personally, I find the sites along the North Cascades Highway to be of most interest, although not necessarily the best options (if it’s even possible to settle on one “best” option). They have paved road access, high elevation north-facing terrain, and are still mostly within day driving distance from north Seattle and Everett. Of course, however, the North Cascades Highway is closed during the winter due to avalanche dangers. When this study was written in 1970, the highway was still under construction and it was not yet determined if it would be open throughout the winter or not. But assuming it was kept open and roadless areas were not a factor, Cutthroat Pass has great potential. Could the North Cascades Highway be kept open in the winter? At least from the west side to this location? Possibly! More on that in a future post.

Overall, I found the North Cascades Winter Sports Study insightful to understand the criteria used to assess ski areas as well a piece of history from when the future of the North Cascades was much more up in the air. Years of land restriction legislation have made many of the sites it studied untenable in the present day but its overall conclusions about successful ski areas in Washington being smaller, local mountains and population growth eventually catching up to capacity at existing mountains are spot-on 50 years later.

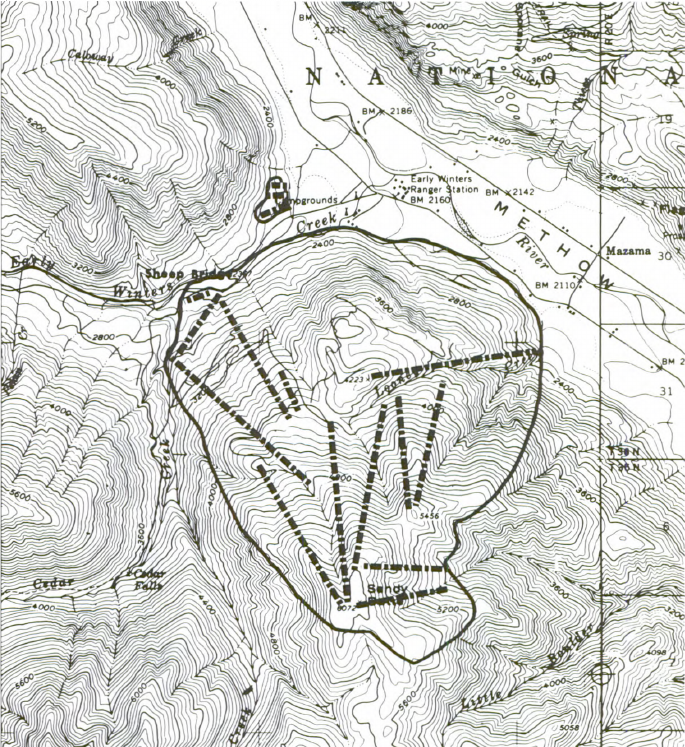

Early Winters Proposal

None of these studied sites ended up being developed, but the pages of the North Cascades Winter Sports Study were not the end of the story for one of the sites. Sandy Butte located next to Mazama was the site of the Early Winters ski area proposal and an impressively large proposal it was. Over 30 years and tens of millions of dollars, the site was attempted to be developed complete with a Supreme Court case weighing in. Ultimately, the project was blocked and it is for that reason it serves as a good case study for the roadblocks that ski areas in Washington collide with.

On the heels of the North Cascades Winter Sports Study, the North Cascades Recreation Plan designed Sandy Butte as an area for ski area development. In 1972 investors formed Methow Recreation, Inc. (MRI) to develop the ski area in coordination with the county. The primary benefit of the Sandy Butte location was the plentiful amount of private land surrounding it. This allowed for a large Colorado-style development.

In 1974 the Aspen Skiing Company bought options for MRI’s stock and the real estate that had been acquired with the goal to develop the ski area now given the name Early Winters. The ski area that was proposed would have been large, even by today’s standards. Featuring 16 chairlifts, it would have occupied 3,900 acres of Sandy Butte.

From 1976 - 1984, the project was effectively on hold due to ongoing broader legal battles around RARE I and RARE II. During this time period, the forest service was unable to issue development permits for the roadless areas contained on Sandy Butte.

With the resolution of these legal issues, in 1984 the forest service granted the permit for Early Winters. Later that year, the Methow Valley Citizens Council, the Sierra Club, the Washington Environmental Council, and the Washington Sportmen’s Council file an appeal against Early Winter’s environment impact statement (EIS) for being insufficient to address all required concerns.

By 1985 Aspen had become wary of the prolonged legal issues and sold their interests in the project to the Bellevue based Hosey Group.4 It’s here that the legal games really begin.

| Year | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1985 | First EIS appeal dismissal | The forest service dismisses the EIS appeal brought forward on behalf on the environmental groups |

| 1986 | Second EIS appeal dismissal | The US District Court in Portland dismisses the EIS appeal for a second time |

| 1986 | Second EIS appeal | The environmental groups appeal to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals |

| 1987 | EIS found insufficient | The court finds that the EIS was insufficient on the grounds of a worst-case analysis not being sufficiently considered |

| 1988 | Appeal to the Supreme Court | The Hosey Group and forest service appeal the case to the Supreme Court in Robertson v. Methow Valley Citizens Council |

| 1989 | Supreme Court ruling | The Supreme Court unanimously rules in favor of favor of the forest service. A supplemental EIS must still address the non-appealed issues but this cleared the way for development to proceed. |

| 1989 | Water rights | To complicate matters further, water rights in the valley become an issue |

| 1992 | Bankruptcy | The Hosey Group runs out of money for the project and interests are transferred to their lender, R.D. Merrill Co. |

| 1993 | Skiing eliminated | The Merrill Co. formally drops any plans for downhill skiing at the site |

The battle continued on until 2000 around the possibility of a resort development focused on other activities such as golf. Despite environmental reviews being completed and permits being issued, the project was ultimately killed by a protracted legal battle that drove the developers to bankruptcy. Meanwhile, Aspen Skiing Co. took the money for the project and instead developed Blackcomb, BC.5

My opinion on the matter is that as great as it would have been to have a destination style resort in Washington, Early Winters suffered from being the wrong development for the area. Mazama is a difficult area to get to, especially in the winter. It is too far from the Western Washington population to be useful as a day trip location, possibly even as a weekend trip location. For out of state visitors, the travel from SeaTac to Mazama would involve multiple mountain passes and hours of driving. With the North Cascades Highway closed in the winter it made a such a large development in a remote area of Washington too large. Early Winters was likely a victim of its own grandeur. Had the plan been for a more modest, local or even regional ski area focused on serving the Methow Valley, Chelan, Omak, and possibly Wenatchee, it may have encountered less resistance and have been built and expanded over time to keep up with demand. It serves as a case study for the difficulties in getting any ski area project off the ground 40 years ago let alone today.

In 2021, the Cedar Creek fire burned much of the area that Early Winters would have sat on. Of course if it had actually been developed more fire protection would have been in place but another factor to consider is that ski areas on the eastern slopes of the Cascades have to contend with summer wildfire hazards as well.

Mountains of Red Tape

Aside from land restrictions preventing development of ski areas in the Cascades, there are general regulations that would need to be adhered to for any potential development.

In 1970, National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was passed. This law required that federal agencies consider the environmental impact of projects before issuing permits or making final decisions. If a project is considered to “significantly affect the quality of the human environment,” as ski areas are considered to do, then an environmental impact statement (EIS) must take place. At its core, an EIS is a sensible document to require for any significant project. It is a tool to help with decision making of the project and to consider alternatives to the proposed project. The issue, however, is that EISs have become weaponized for activist groups to oppose any development that does not maintain the status quo that they prefer or benefit from. In other words, it has given significant power to NIMBYs.

Consider a recent case from February of 2022 where a story made the rounds in the news about University of California, Berkeley not being able to admit more students because of a lawsuit from a neighborhood group, Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods, which argued that the university had not provided enough information on the traffic and environmental impact of a student housing project.6

Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods sued the university in 2019 to stop the project because it said the university had not provided enough information or assurances about how the project would alleviate the housing crisis or affect traffic, noise and other environmental concerns.

Granted, this was a result of California’s state-level version of NEPA, CEQA or the California Environmental Quality Act, but the point stands about how an issue that should be so obviously moved forward with, increased student housing in the Bay Area, hits major legal roadblocks due to the weaponization of environmental impact statements.

Early Winters

This is, of course, not a post about California’s housing issues so let us consider more in depth how this plays out with a ski area. Specifically, how the Methow Valley Citizens Council took their fight against the EIS of Early Winters all the way to the Supreme Court in Robertson vs. Methow Valley Citizens Council. Specifically, when first appealed to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, it was ruled that the EIS was inadequate due to:

- NEPA imposes a substantive duty on agencies to take action to mitigate the adverse effects of major federal actions.

- Every EIS must include a detailed explanation of specific actions that will be taken to mitigate adverse impacts.

- If the Forest Service had difficulty obtaining information adequate to make a reasoned assessment of the project’s environmental impact, it had an obligation to make a “worst case analysis” on the basis of available information, using reasonable projections of the worst possible consequences.7

Upon appeal to the Supreme Court, that decision was unanimously overturned such that:

- NEPA does not impose a substantive duty on agencies to mitigate adverse environmental effects or to include in each EIS a fully developed mitigation plan.

- NEPA does not impose a duty on an agency to make a “worst case analysis” in its EIS if it cannot make a reasoned assessment of a proposed project’s environmental impact. Under conditions of scientific uncertainty, an agency must comply with the CEQ’s new regulation to project “reasonably foreseeable significant adverse impacts.”7

Both of the above case ruling summaries are taken from An Adequate EIS under NEPA: Deference to CEQ; Merely Conceptual Listing of Mitigation Leads Us to a Merely Conceptual National Environmental Policy which is a good summary and commentary on the whole case (I can’t say I agree with the conclusions made by the author, but I respect the point of view). If you would like to decide for yourself, the full Early Winters final EIS is available.

In the end, despite a loss at the Supreme Court level, the Methow Valley Citizens Council got the end result they were hoping for: by weaponizing the EIS process and tying down the developers in legal battles, eventually the project ran out of money. Even with a green light to proceed (other issues such as water rights still outstanding) the project still died.

Mt. Pilchuck

The Mt. Pilchuck ski area, located outside of Granite Falls, operated from 1956 to 1977. Pilchuck is special in that its terrain is great for skiing and its 5,344ft summit is quite high elevation for its location on the far western side of the Cascades. In fact, it’s only a ~45 minute drive from Everett, considerably closer than any other ski area.

It is commonly said that Pilchuck closed due to being too low elevation and more rain falling than snow, but this is not the case. Indeed, its last year of operation was 1977, at the time the worst snow year on record. As I noted in my previous post on the analysis of Cascade snowpack that 1950-1976 period was a high point of snowpack in the Cascades. It certainly benefited from that increased snowfall but Pilchuck still enjoys a healthy amount of snowpack in recent years. It is a commonly used ski touring area, even into the spring when the summer trailhead opens.

Pilchuck is unique in that it is split between both federal and state lands. Thus, the ski area had to contend with obtaining permits from both the forest service and Washington State Parks Commission. According to two former ski patrol directors in the ski area’s final seasons, John Goldthorpe & Timothy Berndt, the true cause of the closure was bureaucracy rather than snow or financial issues as they wrote in The Mount Pilchuck Ski Area Story:

The Mt Pilchuck ski area was born in 1951, when the state parks commission gave a permit to the Mt Pilchuck Ski Club to develop a ski area. It’s not clear what, if any, facilities the club installed at the time, but the authors write that “in 1953 a lack of snow caused the closing of the ski area.” Following this attempt, the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission (WSPRC) obtained a special use permit from the U.S. Forest Service (USFS) to develop and maintain a ski area at Cedar Flats.

The Mt Pilchuck Ski Area, under this new agreement, was launched by John Colter and his mother in 1956. The area began with one rope tow. The Mt Pilchuck Ski Patrol was started that year. In 1958 the day lodge was constructed. Also in 1958 the entire area legally became the Mt Pilchuck State Park. Creation of the park involved a land exchange agreement between USFS and WSPRC, but the exchange never took place. This led to problems later. By 1963, Pilchuck had three rope tows.

The main chairlift was built for the 1963-64 ski season and the lower chairlift was added in 1967, giving Mt Pilchuck Ski Area one of the largest vertical rises in the Northwest. The authors describe a pattern of snowfall extremes, with lean snow years and years with too much snow to operate. Ownership of the mountain concession rights changed hands several times, the final owners being Steve Richter and Heather Recreation, Inc.

The winters of 1977 and 1978 were poor snow years. In 1976-77, the area was open 2-1/2 months and in 1977-78 just three weeks. 1977-78 was the last winter of operation of Mt Pilchuck Ski Area. The following year, in 1978-79, the ski area was passed back and forth between USPRC and USFS, with each agency blaming the other for lack of movement on a concession-lease agreement.

Finally, due to uncertainty over their ability to renew the lease, Heather Recreation, Inc. decided not to continue operation. The authors write that it was the inability of government entities to get together and make a decision that really killed the area, not poor snow conditions or financial problems of the ski area operators. The authors also blame Governor Dixy Lee Ray for working to kill the state’s only winter recreation park.8

If it weren’t for that, it’s likely Mt. Pilchuck could still be operating today. It would never be as large as other ski areas in the Cascades but given its close proximity to Everett, Arlington, and Snohomish it’s possible it could have filled a niche for a smaller, local mountain serving those areas. Night operations could have made it a popular after work destination on weeknights as well. And while elevations below 4,000ft have seen snow declines in recent decades, a lift to the summit of the mountain combined with snowmaking capacity for its base area could have allowed Pilchuck to operate successfully into the future. Alas, it was killed for no good reason.

Stevens Pass

Consider a more recent example as well: In 2008 Stevens Pass proposed the creation of its bike park and expanding the ski area. The goal was to expand the ski area from 12 to 15 chairlifts, add 12% more parking, and construct small lodges/yurts higher up the mountain.9 As any Stevens Pass skier will tell you, the mountain is hilariously overcapacity currently. This was recognized as an issue back in 2008. Despite a majority of positive community support in favor of the expansion, The Sierra Club opposed it believing that Stevens Pass should be required to complete an EIS. Keep in mind that under NEPA an EIS is only required for projects that “significantly affect the quality of the human environment.” In this case, a 12% parking increase and three additional chairlifts in an existing ski area were argued to be significantly affecting the quality of the environment. According to LiftBlog, it took until 2017 for approval to be given for these new chairlifts.10 Unfortunately, not long after Stevens Pass was bought by Vail, whom I doubt has any interest in the project. If it takes nearly 10 years for approval, not even construction, of a modest ski area expansion the future of overcrowding at our ski areas looks grim.

Mission Ridge

Currently Mission Ridge is attempting to undergo a fairly large expansion. It was first proposed in 2015 and here we are in 2022 with it still in the permitting phase with lawsuits currently ongoing. The expansion includes some added ski capacity but also the construction of 613 condo/townhouse units, and 260 single family homes over 20 years. Personally, I think this type of development takes away from the local, day use sites that primarily exist Washington in but the advantage of privately owned land is the freedom to do projects such as that. We’ll see how long it takes for the lawsuits to be resolved and construction to begin on this project.

What this gets to is a larger societal problem that the United States has seemingly fallen into: we can’t build big things any more. While the merits of NEPA and EISs are certainly strong and worthwhile, how they are wielded by activist groups has become a drain on our ability to change the status quo for just about any major development project. It is certainly important to understand the environmental impact of any project but when these reports are used as a method to simply stall progress by exercising a veto power for one group of people they become a hindrance to progress and create undue delays in projects that balloon costs and time to completion. Some type of reform to prevent abuse may be necessary.

This extends not just for ski areas, but for nearly every development project. Be it housing in our cities (upzoning for increased density), transportation projects (light rail and high-speed rail), renewable energy (solar and wind farms), etc. Patrick Collison maintains a list of major projects accomplished in short periods of time He notes that all of the physical infrastructure projects occurred prior to 1970. Compare that to a present day project:

San Francisco proposed a new bus lane on Van Ness in 2001. Its opening was delayed to 2022, yielding a project duration of around 7,600 days. “The project has been delayed due to an increase of wet weather since the project started,” said Paul Rose, a San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency spokesperson. The project will cost $310 million, i.e. $100,000 per meter. The Alaska Highway, mentioned above, constructed across remote tundra, cost $793 per meter in 2019 dollars.11

This is a much larger topic than this post is about of course and one that there is no easy solution to, but for our country to move forward we will need to find a way to balance environmental impacts with necessary development projects. This is required not only for a basic, functioning society but also for building the adaptions required for addressing climate change. I digress.

Wilderness areas thoughts

A fair amount of criticism has been directed towards wilderness areas in this post. It may seem that I am against them, but personally I find wilderness areas to be extremely valuable and am grateful for their existence. They provide vast amounts of public land for recreational purposes that is fairly easily accessible for the avid outdoorsman at a time when our national parks are overcrowded. For congress to set aside these lands and leave them in their natural state is a noble and worthwhile cause that should be continued by us and our progeny.

When considering the state of play in the 1960s with how we treated our mountains, the 1964 Wilderness Act is clearly understandable as excellent foresight on behalf of congress at the time. You need not look far for to understand the horrors of this era:

The above being old growth tree logging taking place in North Bend, WA in the 1960s. While I doubt anyone other than the logging industry wants to see a return to that era, we do need to acknowledge the difficulty that wilderness and roadless areas have created in expanding ski area capacity to keep pace with population growth in Western Washington. Considering that the overlap of high elevation land in close proximity to Western Washington and land free of wilderness and roadless area restrictions is near zero we need to accept that realistically for new ski capacity to be added in the Cascades it will likely need to come from a re-drawing of wilderness areas.

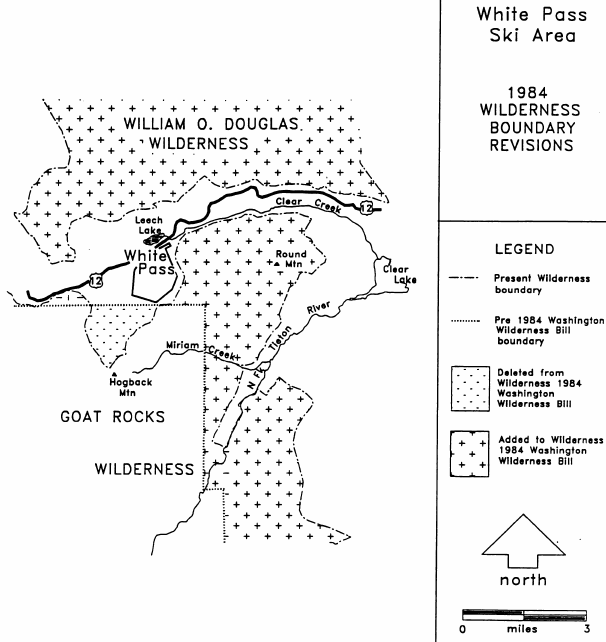

Believe it or not, there is precedent for this, right here in Washington to boot. The Washington State Wilderness Act of 1984 added a great deal of wilderness area in the Cascades but there was one notable removal: 800 acres from the Goat Rocks Wilderness adjacent to White Pass. This allowed for the Hogback/Paradise Basin expansion which opened in 2010 to take place (yes, this was over 25 years in the making!). This expansion doubled the size of White Pass and provided much needed additional capacity. The final EIS for the expansion from 1990 remarks that the Congressional Record for the Act contains the following justification for the deletion:

The 800 acres deleted from the existing Goat Rocks Wilderness have significant potential for ski development and should be managed by the Secretary of Agriculture to utilize this potential in accordance with applicable laws, rules, and regulations.12

How did this come to be then? The EIS goes on to state that in 1989 a letter to the Wenatchee Forest Supervisor, Sonny O’Neal, Representative Sid Morrison explained his intentions:

Early in the 1980’s, I was approached by numerous constituents through several meetings on the desirability of expanding the skiing potential at White Pass. Everyone involved was associated with the White Pass Ski Company as employees, officers, or customers . In other words, we were talking about downhill skiing and the potential for expanding the lifts, runs, and facilities to accommodate the crowds that were increasingly using this recreational opportunity.

At the time, as you may recall, White Pass was on the map because of the Mahre twins and their stellar Olympic performances. As a non-skier, I was proud to show them off when they visited the nation’s capital, and they were eager to share with me and congressional staff members the downhill potential for an expanded White Pass ski area. Other members of Congress gradually shifted from resistance to modifying existing Wilderness boundaries to realization (1) that an expanded White Pass area was truly the highest and best public use for that portion of the Goat Rocks, and (2) that I was more than willing to expand the Goat Rocks significantly to offset the modest loss of acreage in the summit area.12

Representative Morrison put it best when he wrote “an expanded White Pass area was truly the highest and best public use for that portion of the Goat Rocks.” Indeed, “highest and best public use” should be the metric used to gauge these lands.

The 1984 act added 23,000 acres to the Goat Rocks Wilderness alone while removing just 800. With that 800 acre removal White Pass was able to be doubled in size providing increased recreational opportunities for the people of Washington. The fact that the act was adding far more land than it was removing helped it remain politically tolerable. Land that had been set aside the original 1964 Wilderness Act was being released for recreational use of a future generation while additional land was being added for another future generation to choose what they believe the best use for it will be.

Conclusions

It is here that I must switch from a mostly objective look back at legislative history and become subjective. In order to answer the final question this post set out to answer, what needs to happen for future expansion?, we have to consider the nearly all of the viable ski area land in the western Cascades is located within wilderness areas. Yes, some existing ski areas, like Stevens or Crystal, could expand without expanding into wilderness areas, but others such as Baker and Alpental, cannot. And if a new ski area were to be built, especially one at a high enough elevation to avoid the worst effects of climate change it would need to be on land currently within a wilderness area.

With that in mind, and I know this is controversial, here in 2022 a similar decision to the White Pass / Goat Rocks deletion could, and I argue should, be made. We, the present stewards of the Cascades, may decide that the highest and best use for some of the land that was previously preserved for future use is, in fact, expanded recreational opportunities. In exchange for development of this land we preserve an equal or greater amount of land elsewhere in the Cascades for those that come after us.

We should first explore all options to avoid the unnecessary declassification of any wilderness. There may be some options to do so which I will explore in the final post in this series, but in all likelihood some redrawing of wilderness areas would be necessary.

In summary, there are compelling reasons for why a reclassification of small sections of wilderness to allow for increased winter recreational opportunities may be warranted:

- Nearly all land viable for ski area development on the western slopes of the Cascades is protected. Allowing for a closer location to the population center of Western Washington would result in lower carbon emissions resulting from traveling as opposed to traveling to currently unprotected lands on the eastern slopes should those be developed or even from longer trips into British Columbia or Montana/Utah/Colorado.

- As our lower elevation ski areas, namely Snoqualmie Pass, become non-viable ski areas due to climate change the capacity they provide would need to be replaced elsewhere at higher elevations.

- The deletion of any wilderness land in one section of the Cascades could be swapped with an equal or greater amount of land elsewhere in the Cascades making it a neutral or net-gain of wilderness area acreage.

- Reclassifying wilderness does not mean opening it to commercial resource extraction. It could instead be reclassified as a National Recreation Area and given covenants on what it may be used for and to prevent reckless commercial developments, similar to what was done in the 1984 act to create the Mt. Baker National Recreation Area.

- Developing an area for recreational purposes implies a degree of conservation itself. As opposed to clear cut logging, for example, which would defeat the purpose of the recreational area in the first place. In the case of a wilderness area land swap this would mean even further land is preserved in some capacity while still allowing it to be used and enjoyed by the population.

It is important to keep the scale of this type of a proposal in mind. Washington has 4,351,872 total acres of wilderness areas13. In the White Pass example above, the ski area was doubled in size by reclassifying just 800 acres. Applying this to each of the six ski areas in the Cascades would be ~5,000 acres or 0.1% of wilderness land (assuming all of that expansion land was to come from Wilderness areas, which in reality it would not). That’s a small price to pay for vastly increasing the size of our ski areas to keep pace with population growth.

The proposed Roadless Area Conservation Act of 2021 by Washington’s own Senator Maria Cantwell is an opportunity to address these issues. This bill adds protection for vast amounts of land. Adding in some small wilderness adjustments to allow for ski area developments would be a worthwhile trade to make in exchange. It would likely take decades between the passage of a wilderness area adjustment and skiers loading onto a newly built chairlift. If we are to plan for 10-15 years down the road that process must start now. And if a wilderness area adjustment is necessary to facilitate it then it should be as minimal as possible which would mean identifying expansion and new development locations now. When the time comes there will then be viable locations available to provide an ever growing population the access they need to be able to appreciate the same recreational opportunities as we currently enjoy in the mountain range in our backyard.

Through this Washington has the opportunity to be a leader on sustainable ski area development both on minimizing environmental impact and to decarbonize a carbon-intensive industry all while simultaneously allowing for growth and addressing the affordability problems faced by the industry as well. The question is what does that model look like and where exactly could these expansions take place? The third and fourth posts in this series will attempt to answer those questions.

Sources

A special thank you to Lowell Skoog for his Alpenglow Ski Mountaineering History Project bibliography. His well documented research made freely available on his website has been a wealth of information to myself as jumping off points for further research. His book, Written in the Snows, is an excellent journey through the history of skiing in the PNW.

-

A Battle Looms: Skiers vs. Conservationists, Walt Woodward, The Seattle Times, October 27 1968, page 92. ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

U.C. Berkeley Says It May Have to Cut Student Admissions by Thousands ↩

-

An Adequate EIS under NEPA: Deference to CEQ; Merely Conceptual Listing of Mitigation Leads Us to a Merely Conceptual National Environmental Policy ↩ ↩2

-

Activist group opposes plans to expand Stevens Pass ski area ↩

-

Final Environmental Impact Statement, White Pass Ski Area Proposed Expansion ↩ ↩2