Last year I wrote extensively about the politics of ski areas in Washington and a vision for the future of skiing in the PNW. One of the topics that came up in both of those posts was Mt. Pilchuck. Namely its history as a ski area and the potential it has for the future. This made me want to explore more on the possibility of reestablishing winter access to Mt. Pilchuck.

First off, for readers who know the history of Pilchuck, this is not a post about re-opening the lift-served ski area that was once the Mt. Pilchuck ski area. The proposal being made here is more modest: specifically reestablishing winter access to the previous ski area parking lot and current summer trailhead. Yup, that’s it. Doing that alone could have a material impact on expanding winter recreational access in the Snohomish county area through expanded high elevation snow access for ski touring, snowshoeing, sledding, and general snow play areas for families.

Mt. Pilchuck History

Before getting into future proposals it’s worth taking a moment to consider the history of Mt. Pilchuck and how we got here.

Sometime between 1913 and 1921 (accounts differ) the fire lookout still on the summit of Pilchuck was constructed.12 The fire lookouts were, of course, built primarily for fire detection. Given that this is not a concern in the winter, they went unstaffed for those months. There were also far more fire lookouts in addition to forestry/mining cabins at lower elevations. Many of these do not exist anymore due to natural decay after being abandoned or intentional destruction due to wilderness area regulations. However, in the early days this network of primitive cabins allowed ski touring parties to use the cabins/lookouts for extended winter expeditions throughout the Cascades. In the case of Pilchuck, the first known ski descent of the mountain was made in April 1933 by a group of Everett Mountaineers having noted the area for it’s suburb skiing at the upper elevations of the mountain.1

Fast forward to the 1950s when a logging road was built to the Cedar Flats area on the north side of Mt. Pilchuck. This access allowed for the Mt. Pilchuck ski area to be established in 1956 with a single tow rope.3 Throughout the next decade the Pilchuck ski area added two chairlifts with lights for night skiing, more tow ropes, and a day lodge. In fact, at the time Pilchuck had one of the largest vertical drops of all ski areas in the PNW.

Pilchuck in operation

The trouble with Pilchuck, however, proved to be its elevation. With a base area elevation of only 3,100ft, and one chairlift that descended from there, it would often be raining where other ski areas would be snowing. Some years this was not a problem, like in the 1963-1964 season when the top of the chairlift had a snowpack of a whooping 52ft,4 but in other seasons such as the worst snow year on record for the Cascades, 1977-1978, the ski area was only open for three weeks. This year also happened to be its final year in operation.

So why then is there any potential for Pilchuck as a quality skiing location if the snow is this inconsistent and the ski area was forced to close?

Well, there is a caveat to this story: chairlifts never reached the summit of Pilchuck. There was additional, higher elevation terrain that the ski area could have, and wanted to, expand into. Moreover, digging deeper into why it closed we start to see where the politics came into play, which arguably were the primary reason for its closure.

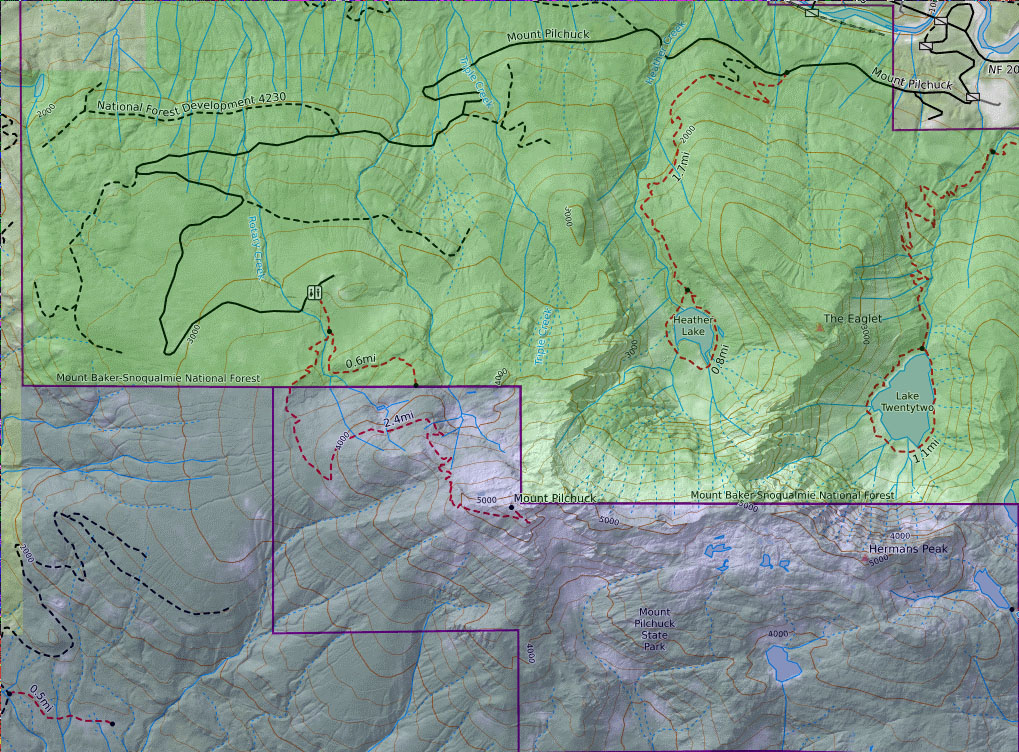

I go more into detail on my post on the politics of ski areas, but in short Pilchuck was closed mostly because of bureaucracy rather than lack of snow. Pilchuck is unique in the Cascades in that it sits partly on both state and federal land. Consider the map below from Caltopo. The green areas (the road and first quarter of the summer trail) sit within the Mount Baker-Sqnoqualmie National Forest and is subject to the whims of the federal Forest Service. Whereas in the purple area, the rest of the summer trail to the summit sit within Washington’s Mount Pilchuck State Park.

What this meant for the ski area was permitting from both the USFS and the Washington State Parks Commission in order to operate. After the poor snow year of 77-78, the ski area knew they had to expand into the higher elevations in order to survive and attempted to do so. However, this would have been on the USFS land and the Forest Service denied the expansion with Joe Nadolski of the Forest Service stating in 1979:

It’s not that we don’t want to see skiing up there. It’s just that we haven’t seen much skiing there since the area opened. That’s the major reason for rejecting the lease renewal and expansion proposal. It’s a low altitude area and it’s often that there’s no snow. We weren’t responsible for Pilchuck’s closure the past two seasons; the weather did them in.5

In my opinion, this was an extremely poor and short sighted decision made in the aftermath of literally the worst snow year on record for Washington. It’s commonly said that Pilchuck closed because of lack of snow, but in reality the ski area operators wanted to expand and continue operations, but the Forest Service explicitly prevented them from doing so.

40+ years on as well, we have the snow and the demand for skiing; killing skiing on Pilchuck was a huge mistake. In fact, if Pilchuck had been allowed to expand operations to the summit, and potentially install some snow making capacity at its base, it would be reasonable to assume that it could still be operating today. It would never be as large as the other ski areas in the Cascades, but given its close proximity to the Seattle population it would have an ample supply of skiers looking for quicker trips to the slopes than driving all the way to Stevens.

Today very little evidence of the ski area remains. The day lodge was torn down after years of vandalism. The smaller rentals building was quite literally driven down the mountain circa 1983. Today it sits along the shore of the South Fork Stillaguamish River.

Beyond that, the chairlifts were bought by Crystal Mountain and relocated. Some of their footings are still visible along the summer hiking trail today. Otherwise, here in 2023, the only recognizable remains of the the ski area is the parking lot / present day trailhead. Since the closure the forest has reclaimed the area cleared for the chairlifts and ski slopes to the point that it’s nearly indistinguishable from the surrounding forest. In the photo below the red square denotes the parking lot. The chairlift would have extended perpendicularly up and down from there.

This photo was taken on May 16th, 2021. Don’t let the seemingly lack of snow imply this is typical of a mid-winter snowpack here. Even this time of year the top 1,500ft is still excellent skiing.

This photo was taken on May 16th, 2021. Don’t let the seemingly lack of snow imply this is typical of a mid-winter snowpack here. Even this time of year the top 1,500ft is still excellent skiing.

Current Access

In the years since the ski area closed, the area has mainly been left unmaintained. The trails receive more or less the same level of attention as any other hiking trail in the Cascades does. The road itself is in an absolutely atrocious condition (more on this later), but most notably for the purposes of skiing, the road to the former ski area parking lot is closed in the winter with it being gated closed at the Heather Lake trailhead.

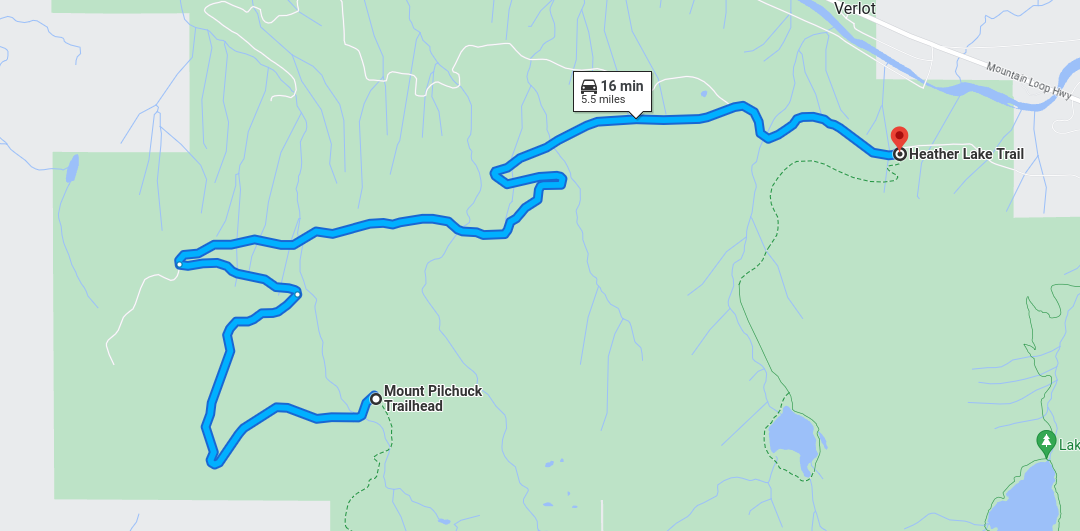

In terms of ski touring access this closure is especially problematic. The Heather Lake trailhead is located at only 1,300ft whereas the summer trailhead is at 3,100ft. That’s 1,800 vertical feet to effectively get to the start of your tour. To the summit would be nearly exactly 4,000ft. And while we would all love to be able to bang out 4,000ft+ days (assuming you want to get more than one run in for all this work), for the non-diehard skiers that may prefer to do more relaxed days under 4,000ft/day, getting to the summer trailhead is nearly half of your day alone and in conditions that are almost certain to be marginal at best.

Moreover, by horizontal distance walking the road is 5.5 miles to the summer trailhead from the gate. While it’s possible to cut some switchbacks and tour up the former ski area cut in the forest to reduce this distance, this becomes increasingly difficult as the forest continues to grow in and in times with less snow it may not be possible to skin this lower elevation portion.

Given that the potential allure of Pilchuck is close and easy access to high(-ish) elevation snow, the entry tax of just getting to the summer trailhead means it’s usually more worthwhile to visit other locations with easier access instead. In years and decades past when we had far fewer people visiting our mountains in the winter that was fine, but the entire point of this article is that this road closure creates a wasted opportunity to better disperse crowds in our otherwise overcrowded winter-time mountains. Let’s take a look at why another snow access point is needed.

Why create more winter recreation access?

As I discussed in a previous post, Washington’s population has grown by 50% since 1990 with another 30% expected by 2050.6 Accordingly, this has put stress on recreational access in the Cascades. This is true for summer recreation, but especially so for winter recreation due to the limited number of access points to high elevation snow.

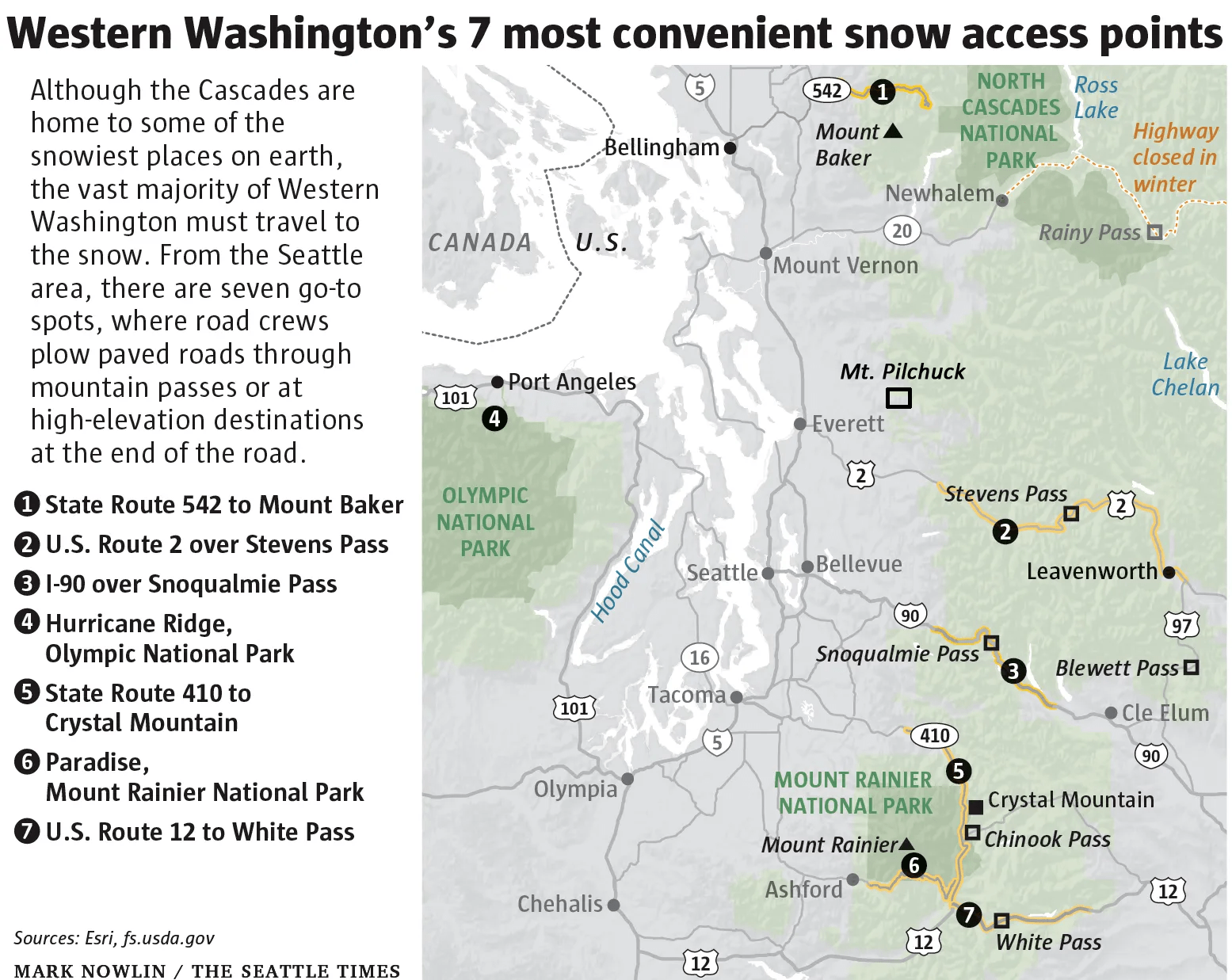

In fact, there are really only seven high elevation snow access points in Western Washington:

With the exception of Paradise, each of these also correspond to a ski area. For ski touring, this has the downside of using the same roads and parking lots as these ski areas when they are already vastly overcapacity themselves.

It’s not only ski touring, however. Other forms of winter recreation including snowshoeing, sledding, and general snow play areas for families with children are also in high demand. Having places to separate these activities from the ski areas would help relieve pressure on the ski areas while also allowing for more opportunities to partake in them.

Why is Pilchuck the right place for this?

So then, why is Pilchuck the right location to create this access?

For starters, Pilchuck is a notably high elevation mountain for being so far on the western edge of the Cascades. This brings the advantage where it’s more easily accessible to North Seattle and Snohomish County residents than many other areas located deeper in the Cascades. Likewise, since it sits along Mountain Loop Highway, rather than a mountain pass, the amount of traffic in the area during the winter is minimal. Compare this to the traffic on US-2 through Sultan which even in the winter can add an hour or more to your trip back to Seattle. Expanding winter access along Mountain Loop Highway makes use of an underutilized area of the Cascades in the winter and disperses a small amount of the would-be US-2 traffic elsewhere.

As for the terrain itself, Pilchuck tops out at 5,344ft. While this isn’t anything crazy high for the Cascades, it is at a good elevation for skiing sitting between the summit elevations of Baker and Stevens. I previously analyzed the Cascade’s snowpack over the past 100 years to analyze how it was responding to climate change. The takeaway being that anything over 4,000ft is likely to remain decent skiing for the foreseeable future. While it’s probably not the best location to be considering for the capital investment required to install chairlifts again, it’s not a massive undertaking to plow an existing road either.

Similarly, the terrain itself is excellent for skiing. Obviously it was good enough for a ski area in the past, but even better terrain exists coming off the top of the mountain. The Gunsight Couloir (featured in the photo at the top of this article) is a 40° slope just to the east of the fire lookout. From the bottom of it, and with sufficient snow, the south face of the mountain can be skied lower down as well before skinning back up to ski the north face back down. In fact, large parts of the northern side of the mountain are open faces leading into sparsely gladed runs. All of this makes Pilchuck a popular touring location currently and, I believe, gives it the potential to be even better with a high elevation trailhead open.

The north aspect of Pilchuck; lots of great lines to be had here from the summit towards the trailhead to the west or Larrison Ridge to the east. With sufficient snow there are also chutes that descend into Heather Lake (not pictured here). This photo was also taken in May 2021.

Another notable feature of Pilchuck is the fire lookout at its summit. Like some other fire lookouts in the Cascades, this could be made available for overnight stays in the winter too making it possible to stay at the higher elevation for multiple days without needing to haul as much gear up with you. This assumes it is properly cared for and maintained, of course. Other lookouts that used to be open in the winter for these purposes have since been closed due to neglect, unfortunately.

And finally, while many mountains in the Cascades have favorable skiing qualities, the primary attribute that sets Pilchuck apart is its road access. It was already mentioned how Pilchuck sits off to the side of Mountain Loop Highway, which is already presently maintained in the winter well past the turnoff to Pilchuck. The forest road itself is open in the winter up to the Heather Lake trailhead. This means that in order to establish winter access to the summer trailhead, all that is needed is a little over five miles of plowing.

Moreover, this road weaves its way through the forest. There are no cuts into the side of the mountain, avalanche chutes, or really any significant danger that would require additional mitigation in the winter beyond routine plowing. And at the end of the road is the former ski area parking lot which is decently sized and able to hold a good number of cars for anyone using it on a given day (as opposed to other trailheads where finding parking can be an adventure of trying to not block the road while getting uncomfortably close to a large drop off). Another advantage this road has for winter access is that the top half of it is actually already paved. This is, of course, due to the former ski area; I don’t know if the bottom half was ever paved as it is dirt currently. It certainly would need repairs in areas, but the mere fact that the higher elevations are paved already is a major advantage to keeping it open in the winter.

As for the bottom dirt half, it is worth discussing the current state of that portion because it is… bad to put it mildly. I really can’t overstate how poor of a condition the lower half of this road is. There are potholes on this road that give Heather Lake a run for its money in terms of depth. It is easily the worst actively used forest road I’ve driven on in the Cascades and to make matters worse it is lined end to end with cars on any given summer weekend around the Heather Lake trailhead making it impossible to dodge the potholes.

I’m far from a snowplowing expert, but my feeling is that before this road could be kept open in the winter there would need to be repairs to at least portions of the paved section and major repairs to the dirt section. However, given the popularity of the Heather Lake trail in the summer, this would be a welcome improvement regardless of if it’s kept open in the winter or not. In reality, it may be best to just pave the entire length given its summer popularity and the ease of plowing it would facilitate.

Economics

As with everything in this world, keeping roads open in the winter costs money. So how would this be paid for?

There are two areas in particular that need funding before the road could be kept open to traffic:

- Road repair to improve the lower dirt half and spot repairs to the upper paved half.

- Ongoing funding to pay for snowplowing.

Let’s cover the second item first. Assuming the road was repaired enough to make it feasible to plow in the first place, how would said plowing be paid for?

One option, and probably the easiest, would be a volunteer program. Like many forest roads in the Cascades, simply leave the gate open and let adults be responsible for their own decisions about what they can and cannot make it up. From there, the touring community could potentially self-organize volunteer plowing given that this road isn’t an especially difficult one to keep clear with the lack of avalanche problems.

Another option would be a voluntary donation model similar to the Friends of Hyalite program in Montana. In that program, users of the area donate $20/yr to reimburse the county for 60% of their costs to keep the road open. More research is needed on specific numbers for what would be required here, but this model could likely work well in Washington too. Snohomish county may even be interested if it relieves some traffic along US-2. Plus, unlike Montana, the lowlands of Western Washington rarely get snow in the winter. This means that country snow removal resources are generally more available.

Now for road repairs, this is a difficult issue that there’s not a clear solution for as the road itself sits on National Forest land and funding for our forest roads is stretched thin enough as-is with many roads being essentially abandoned due to lack of funds to maintain them. However, while I was writing this article some news about new logging projects in the area has come out which is planned to expand the Heather Lake trailhead parking from 25 cars to 75.7 Will this also bring along the needed road repairs? That is to be determined, but I’d say it’s a good chance that if the trailhead is being expanded that the road segments around the trailhead, which are the worst parts, would be repaired as well.

As a side note, I know we all generally dislike logging in the Cascades, especially in areas used for recreation, but this is a good reminder of how the forest roads we all enjoy for access to trailheads were quite literally built on the back of the logging industry of yesteryear. When the areas to be logged are second-growth forest that that has become more dense than old-growth forest and is located near towns causing wildfire concerns I think it’s reasonable to make the tradeoff of some logging in exchange for forest health and recreation funding (especially after the Bolt Creek Fire last year demonstrated the ability for this area of the Cascades to produce devastating fires).

Otherwise excluding this new logging project, unless federal funding is to be provided it’s not likely that the Forest Service would be able to fix the lower half of the road let alone asphalt repairs to the paved half. Maybe the state would be willing to pony up some road repair funding since the road is for accessing its state park, afterall?

There is another option, however; one that I think is particularly interesting. Bluebird Backcountry in Colorado is a ski area, but without chairlifts. For day tickets starting at $40 (or a season pass if you choose) you get access to their avalanche-evaluated ski area with marked trails, ski patrol, rental options, and avalanche courses, which is all only accessible via skinning.

Given the ever growing popularity of ski touring, a similar model in Washington could work excellently here. Having a spot close to Seattle where folks new to touring could rent gear, get instruction, and try out touring in a professionally avalanche-evaluated (not necessarily mitigated) area could be a huge benefit to the sport while also instilling good habits in new folks from the start.

In exchange, part of the revenue from this ski area would be used for road repairs and snowplowing. Plus, by definition, the only infrastructure needed is a small, even temporary building for rentals, tickets, and patrol. Initial set up costs would be minimal compared to that of a lift-accessed ski area. This model provides the funding benefits that a commercial operation provides but without the large capital investment of chairlifts.

Conclusions

Overall, the potential access that Pilchuck could provide for numerous forms of winter recreational in Western Washington is extremely promising. It’s in the right location, has good road access, great ski terrain, permissive land zoning, and a history of skiing. All we need to unlock this potential is winter road maintenance.

So could we make this happen? Last year I wrote a series of articles on the potential and pitfalls of expanding lift-served access in Washington. Most of this being pie-in-the-sky type ideas. Compared to that, re-opening Pilchuck seems like a very down to Earth type of proposal. Since last year I’ve had a handful of people reach out to me regarding ski access in Washington. One of the topics we’ve always come back to is how there is a lack of advocacy groups for skiers here, both backcountry and lift-served. We’ve traditionally relied on ski areas to provide this access for us. However, in the rapidly evolving world of corporate consolidation in the ski industry it likely will end up being in our and the sport’s best interest for a grassroot skiers organization to come together to work with the federal and state agencies to bring proposals like this one to fruition. Are you interested?

Sources

-

To get to iconic Pilchuck lookout, hikers must brave ‘hell on wheels’, The Daily Herald ↩

-

Written in the Snows, Lowell Skoog, p186 ↩

-

Forest Service wins Stillaguamish logging suit over conservation group, The Daily Herald ↩